|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

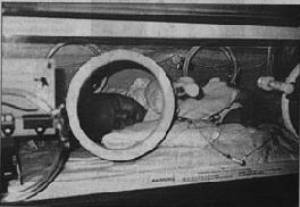

“Before long, Jesse was lying in the neonatal intensive care unit, hooked up to a breathing machine with tubes coming out of him everywhere,” recalled Shelene. “He was getting everything from a spinal tap to a blood transfusion. Chris and I prayed for Jesse to be protected and for God to show us the miracles that could come out of this tragedy.” It was three days before they knew Jesse was going to live. After 17 grueling days in the NICU, Jesse went home again. Shelene remembers waking up countless times with her body straddled across Jesse’s crib, having fallen asleep while monitoring his breathing. |

|

One month later, Jesse began projectile vomiting. A CAT scan revealed hydrocephalus—excess fluid in the brain—a side effect of meningitis. He was rushed to surgery, where a 3-inch shunt was placed in his brain to drain the fluids through a permanent tube down his neck to his stomach, where the tube uncoils as he grows. Seven months later, the Keiths had to hand their baby back to the neurosurgeon for a second brain surgery because the shunt malfunctioned and had to be replaced with a larger one.

Blonde and dimpled, Jesse today is an energetic and healthy 2 year old discovering words. But his barely survived first year has taken many tolls—some financial, because the family wasn’t able to work during much of that time, and some emotional.

“When we found out this might have been preventable, we were furious. We decided this was our cause,” Chris said, “and we weren’t going to stop until everyone knew about Group B strep.”

Shelene added, “My OB never tested me or even mentioned that Group B strep existed. Our prayers have been answered with Jesse’s health and with The Jesse Cause, and now we want to make sure other parents don’t go through what we did.”

After Jesse’s birth, when the Keith family music ministry performed throughout Ventura County, they also told Jesse’s story, passed out pamphlets with GBS details, and urged all pregnant women to be tested.

Local Christian radio station KDAR offered support by airing more than 15 Jesse Cause interviews as well as playing songs from To The Cross, Chris’ CD. Oxnard’s Babies R Us store gave them a table at their health fairs and arranged for the Jesse Cause pamphlets to be carried in their store information centers statewide.

Before too long, wherever the Keiths performed, people in the audience began to come up to them with their own GBS horror stories or with thanks because The Jesse Cause had led them to be tested and treated.

Greg Totten, Ventura County chief assistant district attorney, came forward as a volunteer to help the Keiths draft a legislative proposal to mandate screening for GBS as part of regular prenatal care. Local grant writers volunteered to help The Jesse Cause Foundation find full funding to realize its goal to distribute 29 million pamphlets in several languages every quarter to 145,000 maternity-related facilities.

Shelene tried to influence doctors to understand the importance of universal screening. “Early on, I was invited to join a GBS panel at a family care physician’s conference. I was facing about 70 doctors and telling them what happened with Jesse and how simple it was to change and they all looked through me. I clearly did not make an impact.”

For The Jesse Cause, that was a turning point. “From then on I knew we had to have a different strategy,” she said. “We had to make testing for GBS trendy with mothers nationwide and then the doctors would follow.”

To accomplish that, The Jesse Cause is recruiting celebrities to make public service announcements that will air nationally next month. The Jesse Cause is also working to nail down July 1, 2000 as “National Group B Strep Awareness Day.”

“We know we’re making a difference in Ventura County,” said Chris. “Soon, we’ll make a difference across the nation. It’s our goal to get our pamphlets nationwide by mid-2000 and then worldwide. We want to make Group B strep so public that no one in their right mind wouldn’t test for it.”

Dr. John Queenan, editor-in-chief of Contemporary OBGYN, has written, “Group B strep is the Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde of obstetrics and gynecology. This entity lurks silently in the vaginas of 10% to 30% of healthy pregnant women and poses no particular threat to them. To the fetus, however, it can be devastating….From 5-15% of the infected babies die.”

Only problematic since the 1970s, GBS is a bacteria that lives naturally in the gastrointestinal system and can be carried down to the rectal and vaginal area, usually without symptoms. Women and men can be lightly colonized at any given time, their immune systems eventually winning the battle. People with chronic medical conditions and the elderly are the most vulnerable to losing these battles, as are, of course, newborns.

The risk can be even higher to pregnant women who are of black or younger than 20.

“I was only 19 then. The doctors look at you like you’re stupid, especially if you’re a young mother. No one was answering our questions so my husband and I researched it ourselves. I don’t believe a thing a doctor tells me now without getting a third and fourth opinion. I’m lucky that my child hasn’t continued to have seizures; I think prayer had a lot to do with it.”

~Becky Lawson, Mom to Larry, 6/22/89, GBS Survivor, Ventura, California

The GBS bacteria has an elusive nature. A pregnant woman can test negative, and yet be positive for it weeks later when she delivers. If so, the baby can ingest the amniotic fluid while passing through the birth canal. Having a C-section is no safeguard as GBS can also pass through the placenta.

GBS can affect women who have had perfectly normal previous pregnancies. Having no history of GBS is no safeguard against a current infection.

“I too was never tested nor was I informed of GBS. Afterwards, I was told that I wouldn't have been tested anyway due to not having any history of GBS. So I lost my daughter due to no history. Makes no sense to me.”

~Staci Veaughn, Mom to Shannon, 5/2-4/94, GBS Victim, Jacksonville, Florida

There are two categories for infected infants: early- and late-onset. Early-onset GBS—like Jesse’s—usually hits within the first six hours and up to seven days. Twenty percent of the infections are late-onset between seven days and three months.

“Much the same way parents donate a dying child’s organs, I am hopeful that someone will read about Brian’s late-onset death from GBS and recognize the signs before it’s too late. Maybe a child will be saved in his name. That is my wish now.”

~Maria Macaluso, Mom to Brian, 8/4-29/98, GBS Victim, Wenonah, New Jersey

The test costs between $15-35, and it would be unusual for an insurance company not to cover it. An OB/GYN swabs a woman’s vagina and rectum, and sends the specimen to a lab for a culture process.

“I am furious that the doctor did the GBS test wrong. He only did a cervical culture, whereas a rectal/vaginal culture would have rendered more accurate results.”

~Kim, Mom to Zachary, GBS Survivor, California

The standard is to test in the third trimester between 35-37 weeks to get the results as close to delivery as possible. However, this rarely helps women who suffer early miscarriage, preterm stillbirths or have no prenatal care.

When a woman is identified as GBS positive, she is given intravenous (I.V.) antibiotics four hours before delivery so they can get into her amniotic fluid. Chris Keith observes that doctors don’t always explain the “four hour factor” to the families and if the woman goes into labor quickly, by the time it’s discovered in the chart, it can be too late.

“I was told the IV would be effective ‘instantly.’ I would NOT have laid back down when my contractions started had I known that pneumonia, meningitis or death could happen to my baby. And I would NOT have been driven 45 minutes through rush hour traffic with my contractions 1-3 minutes apart when I could have gone to a hospital five minutes from my home.”

~Marti Perhach, Mom to Rose, Stillborn 7/1/98, GBS Victim, Pomona, California

There’s disagreement about using oral antibiotics during pregnancy. The CDC says it won’t prevent newborns from getting sick, plus some doctors fear building antibiotic resistance. But women are nervous, especially if they have had a GBS child, that they may never get to full term delivery to receive the intended I.V.

The truth is no one knows how many stillbirths and miscarriages are being caused by GBS because baby autopsies are sporadic and GBS is not a “reportable” disease.

“I think that there are so many babies who have died through miscarriages who might have been killed by GBS. My doctors didn’t encourage us to have an autopsy.”

~Marti Perhach, Mom to Rose, Stillborn 7/1/98, GBS Victim, Pomona, California

“Until you have mandatory reporting, you don’t have as good a picture,” said Robert Levin, Ventura County Medical Officer. Mandatory reporting and mandatory testing for Group B strep would have to be instituted by each state’s health department and approved by legislation.

“The state said that I had to contact a mortuary, I had to get an urn, I had to scatter their ashes—but nobody said I had to be tested for Group B strep.”

~Berna Arnold, Mom to Stillborn Twins, 10/10/99, GBS Victims, Moorpark, California

Infants born to GBS mothers are tested and observed for 48 hours and treated with antibiotics if there are signs of infection, though many neonatologists put the infant on I.V. antibiotics immediately and ask questions later.

There are two prevention strategies for Group B strep, causing deadly disharmony in the medical field, and it looks like the reasons have more to do with fear of liability than providing the best medical care.

The “risk-based strategy” only treats women with identified “risks” for general infection at the time of labor— prolonged ruptured membranes (her water breaks) 12-18 hours or more before delivery, premature labor, a fever during labor—or a proven GBS history from a known test or previous birth.

The “screening-based strategy” does exactly the same—only it also cultures all pregnant women, treats them if they’re positive, and doesn’t treat them for a pre-term birth if they’re negative.

Although GBS is not 100% preventable, there is significant evidence that screening can prevent more cases than not screening—for the obvious reason that it tries to find and treat the infected women who have no risk factors like Shelene Keith. If the logic of that is not enough, recent studies have verified that the risk-based strategy will prevent only 40 to 50 percent of GBS babies while screening-based prevents 78 to 86 percent.

Although the CDC officially endorsed both strategies in its 1996 Guidelines, it continually refers, further within the document, to a “combination” strategy being the most effective, the most reasonable and the most economical. It’s vital to understand that the screening-based strategy is, in effect, that combination strategy.

Thus, this risk-based” versus screening-based is perhaps a non-issue obscuring what seems to be the real issue: liability. Doctors who read the CDC Guidelines carefully have no trouble concluding which protocol is really recommended.

Dr. James Caillouette, a Pasadena OB/GYN doctor for more than 40 years, observes, “The establishment does not seem to want the simple screen-based approach, which has been proven effective over and over again. In the meantime, we continue to have dead and damaged babies.”

Doctors who don’t understand the politics involved often think there are real issues of cost, logistics and statistics that make universal screening impractical. Yet, the doctors who are practicing the screening approach seem to have dealt with these issues efficiently.

Dr. Robert Lefkowitz, chief of obstetrics and gynecology at Ventura County Medical Center, is a proponent of the risk-based strategy and thinks of universal testing as a “logistical nightmare.” He voices concerns about “getting a reliable, quality lab,” that doesn’t give ‘false-negatives’ and having a test result locked in his office on a Saturday night.

But, responded Dr. John Keats, OB/GYN Medical Director at Ventura Community Hospital, and a proponent of screening-based strategy, “None of these things are problems if you’re dealing with a reputable, well-established facility like UNILAB. This is not a complicated test.”

UNILAB, the largest in California and one of three national labs that handles most of California’s testing, notes that all completed tests are available to doctors by phone 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

“Logistical problems like these just need to be addressed and are poor reasoning for not doing a test,” added Dr. Keats.

The other major objection to screening is the risk for complications from varying degrees of allergic reaction and antibiotic resistance. Still, the odds of having a fatal reaction to antibiotics is one in 100,000, and, points out Dr. Keats, “These things are being done in a hospital setting where they can be addressed promptly and readily. As to developing resistance, penicillin is a first line agent, not used for everything anymore. You’d have to treat a large number of women before that would be a concern. Compared to the problems of GBS, these problems are relatively minor.”

Given the choice, it’s unlikely that many GBS parents would forego antibiotic treatment that would drastically increase the odds of their baby being born healthy.

The larger ethical issue, say parents of GBS babies, is that OB/GYNs who refuse to screen GBS to lessen antibiotic exposure are improperly withholding the decision-making process from the parents.

“My son is severely multidisabled with a shunt, visual impairment and a seizure disorder. He is also cognitively and mentally impaired. I brought my son to my OB/GYN visits so my doctor would never forget what GBS does since he thought being tested for GBS was not necessary.”

~Nancy Wrobel, Mom to Bryce, 12/02/92, GBS Survivor, Springfield, Illinois

Dr. Lee Hartman, medical director for Blue Cross Insurance, says, “I have no problem endorsing the position that OB/GYNs should inform mothers-to-be about Group B strep. By inform, I mean about what can be done and the controversy about it so adequate decisions can be made.”

When asked if he informs his patients about their option to be screened, Dr. Lefkowitz replied, “We talk about it. I present the statistics and information that’s available. After I talk to them, most decide not to get the test.”

When Dr. Lefkowitz gives his point of view, he speaks convincingly and with great sincerity. “We need to approach things in a scientific, balanced way,” he said. “These issues come and go and the obvious answer is not always the best.” He said that if his wife were pregnant, he would not screen her for Group B strep.

Given that one to two live births per 1,000 have GBS, if an obstetrician delivers 100 babies a year, it could easily take 10 years before he or she personally comes across a Group B strep baby.

This lack of firsthand exposure, combined with the complexities of GBS and the underestimation of its involvement with babies who are never born, has made a deadly formula of rationale for obstetricians that GBS is too rare to worry about.

“Doctors should not downplay anything. GBS killed my twins and nearly killed me. Suffering is not what statistics quote, nor should those statistics be a part of anyone’s life.”

~Berna Arnold, Mom to Stillborn Twins, 10/10/99, GBS Victims, Moorpark, CaliforniaSome doctors have defended not fully informing parents about GBS by claiming they did not want to scare them with something that might not happen.

“I'd rather scare you NOW, and have you leave the hospital with a healthy baby, than to have YOU scared and sad when you have to bury your newborn!”

~Trish, Mom to Franklin, 10/28/98, GBS Victim, Durham, North Carolina

Parents are asking why Group B strep isn’t equal to other diseases that receive automatic testing. Spina bifida and Down Syndrome affect two to three newborns out of 1,000, similar to GBS.

Dr. Lefkowitz says testing for PKU, which affects one baby in 10,000 to 25,000, began after one of the Kennedy children had it. Does Group B strep have to harm the child of a powerful family before it is taken seriously?

Since there was no official protocol for GBS in 1992, it was helpful when ACOG, the powerful American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, published prevention guidelines outlining the “Risk-Based Strategy.”

Four months later, the American Academy of Pediatricians (AAP) endorsed the Risk-Based Strategy, but added that women should be screened, and if positive, treated.

The AAP Guidelines created a liability issue. Could they be upheld in a court case against a doctor who didn’t screen? In May of 1993, ACOG drew the fighting line in the sand and updated their guidelines to clearly state that they did not recommend “routine prenatal cultures” and that the only valid protocol was risk-based.

For two years, confusion reigned and so did Group B strep. Gina Burns, organizer of the Group B Strep Association, worked with the CDC to call a conference in 1995.

Dr. Carol J. Baker of Baylor College of Medicine in Houston was there as one of the pioneers of GBS research (not as an AAP representative, although she had drafted their guidelines). According to Baker, after discussion, there was clear feeling among the participants that the screening approach was the logical strategy. Then it became evident that ACOG had “such a strong opinion about being allowed to use risk-based” that there would not be a consensus.

“And there could be no prevention strategy if there was no consensus,” adds Baker. According to Gina Burns, an ACOG official later told her they had to “protect” their members.

Baker elaborates: “In 1992, there had been several controlled clinical trials that demonstrated that giving antibiotics to a colonized mother could prevent disease in the baby. To me, to turn around and not do that when you had these studies, posed a litigation risk. Nobody said it out loud, but ACOG’s attitude was ‘If we didn’t know who was colonized, we couldn’t be responsible.’ In other words, the concern of litigation made them react negatively.”

Since the CDC is a public health agency with no regulatory power, it published its now widely accepted 1996 Guidelines stating that either of the two protocols were acceptable standards of treatment. Two months later, ACOG amended their guidelines to agree with the compromise, as did AAP in 1997.

“This is the kind of thing that happens in foreign diplomacy,” said Dr. Baker. “If you’re going to get nothing, in fact go backwards, you’re going to compromise.”

Cynthia Whitney, a CDC medical epidemiologist and Guidelines co-author, said, “A combination is what we advocate.”

When asked directly why the summary reads “the CDC recommends use of one of two prevention strategies,” Whitney’s answer is diplomatic: “Doctors tend to look at their own practice and the concerns in their practice. Having a prevention policy in place has increased treatment. Physicians are understanding more and hopefully this understanding is getting passed along to patients. I agree that we have a distance to go before Group B strep becomes a household word.”

“The people I have told have never heard of GBS. I am beginning to think it is a political thing. What kind of political thing I do not know, but if they have known about this since the '70's why don't more of us know?”

~Rhonda, 1999 GBS Mother-To-Be, Indiana

After being told repeatedly that their cases were too hard to prove, angry parents are now starting to find lawyers willing to examine the complex issues of Group B strep. Aided by the existing guidelines, the lawyers are winning seven-figure settlements against medical entities not following either of the two protocols. It is a tangible way to get a message across to doctors that things must change.

“We are angry, and disappointed in the medical community for failing our son with something so preventable. In their infinite wisdom, they stole my son's future and permanently disabled him.”

~Eric, Dad to James, 7/31/98, GBS Disabled Survivor, Southeastern U.S.

Dr. Michael Mah, a neonatologist who is Medical Director of Los Robles Medical Center and a proponent of universal screening, observes, “We no longer practice the kind of medicine in this country that provides all enveloping medical care. You’re now a medical consumer and you have to watch out for yourself to some extent.”

As “medical consumers,” Chris and Marti Perhach of Pomona, California have made an informational video documenting the facts of the GBS stillbirth of their daughter Rose. As they raise funding, they will be sending their video nationwide to the state medical advisory boards, medical schools and investigative television and talk shows.

Chris and Shelene Keith and other parents have tried to interest the talk shows and medical news segments in their GBS stories, but the problems are too complex for sound bites, and pregnancy issues have limited interest. With its upcoming campaign, The Jesse Cause hopes to create national awareness of this preventable tragedy.

The future can only improve for the Group B strep issue, especially with current and upcoming technological advancements.

Many GBS women have early signs of possible infection, often treated incorrectly with over-the-counter anti-yeast medicines instead of antibiotics. A prescription-only home test that will allow pregnant women to screen their own pH levels, created by Dr. James Caillouette, is being considered by the FDA for over-the-counter sale.

Called pHEM-ALERT, it allows pregnant women to report abnormal findings to their doctors, who can then test and treat them for bacterial infections, a risk for pre-term labor and possible indicator of GBS.

Even the risk-based advocates have said they would be open to using a reliable rapid test at labor if it were dependable.

There were some rapid tests several years ago that took themselves off the medical market after the FDA asked them to submit results comparing themselves to the CDC standard. Biostar’s STREP B OIA resubmitted and was approved August 1999, making it the only FDA-approved maternal rapid kit available.

Unfortunately, the false start has made many doctors slow to take a second look. But Biostar is working hard to convince them, as well as mounting a national media blitz aimed directly at women.

The best answer yet could be the promise of a vaccine. Dr. Dennis Kasper and Dr. Carol J. Baker are working on a vaccination for adolescent girls and women of childbearing age that would produce protective antibodies. Clinical trials won’t start until mid-2000 and FDA approval could take it to 2005.

As Dr. Mah said, parents have to be medical consumers and look out for themselves. That’s why The Jesse Cause is bypassing the medical community’s infighting, resistance to change and fear of liability. Chris and Shelene Keith remain focused on educating and empowering women to insist on testing and treatment for Group B strep.

“The incidence of Group B strep infection in this country is a national disgrace,” concludes Dr. Caillouette. “The Jesse Cause and their quest for universal screening should be embraced by all pregnant women, as well as their physicians. If Group B strep happens to you, it happens 100 percent of the time.”